John Rocque’s Survey of London, Westminster & Southwark, 1746.

Surveying London from a church tower. Detail from John

Rocque, Map of London and Ten Miles Around.

Surveying London from a church tower. Detail from John

Rocque, Map of London and Ten Miles Around.

Introduction

The historic base map used by Locating London's Past is John Rocque's Survey of London Westminster & Southwark. It was chosen as the most detailed and accurate representation of the eighteenth-century metropolis we possess; and as the map most likely to incorporate place names that can be identified in other historical documents. It was advertised as being ready for sale on 27 June 1747, but was the result of survey work that had begun more than eight years earlier.

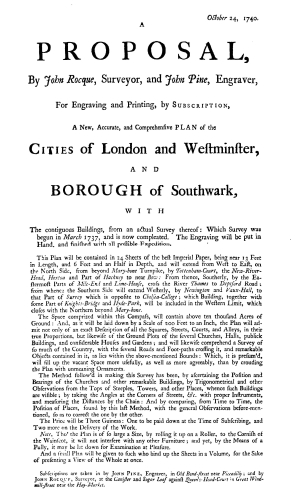

A Proposal, By John Rocque, Surveyor, and John Pine,

Engraver, For... A New, Accurate, and Comprehensive Plan of

the Cities of London and Westminster, and Borough of

Southwark, (1740).

A Proposal, By John Rocque, Surveyor, and John Pine,

Engraver, For... A New, Accurate, and Comprehensive Plan of

the Cities of London and Westminster, and Borough of

Southwark, (1740).

Despite being the best map available, it is neither accurate in relation to the precise layout of buildings and roads in the landscape, nor does it include all the buildings and boundaries present at mid-century. For use on this website, it has been substantially manipulated to ensure that the underlying map sheets join accurately to form a single image; and to 'warp' the map, or 'correct it' to ensure it reflects the underlying geography as recorded by modern map makers. This process relates a single eighteenth-century understanding of the landscape to a modern one, and in the process illustrates the biases integral to Rocque's original map. For a detailed description of the process by which the map was warped and made GIS compliant see Mapping Methodology.

In using Rocque's map in combination with other historical sources, it is important to keep in mind that it is an eighteenth-century interpretation of the landscape, which embeds assumptions about what should be recorded, and what could be ignored. Churches, for example, are recorded in detail, whereas industrial buildings are under-represented.

Physical Description

John Rocque and his then partner and engraver, John Pine, described the map in an advertisement published in 1741:

The scale was 26 inches to the mile, and Rocque estimated that it would encompass over 10,000 acres in area. It was designed as a 'plan', rather than a 'map view', that is it creates a notional point of perspective directly above each point on the map, and depicts all buildings and streets as two dimensional objects. It even records the internal layout of some larger buildings such as St Paul's Cathedral, as if viewed through the fabric of the building.

Rocque was clear from the beginning what sorts of detail he would include on the map:

In the end, the granularity of these details varied from area to area, depending on the density of the built-up cityscape, the pattern of recording practised by the surveyors, and the sharp-eyed diligence of the engraver. The crowded streets of the City forced the surveyors to ignore many minor alleys and courts; while in other areas, such as Lambeth, the open streetscapes allowed details such as the layout of front and back gardens to be indicated. The only pictorial elements included on the map are trees, which are given a late afternoon shadow line pointing due East (a geographical impossibility); a rather random collection of boats on the Thames and in the docks which appear to obey no known rules of navigation or seamanship; and the gibbet at Tyburn.

Because the Court of Aldermen in the City, which was elected on a Ward franchise, subsidised the map's production, ward boundaries are included within the City; while parish boundaries are marked outside. Overall, the map is most accurate for its record of the layout of the West End and City; neighbourhoods where many of the elite subscribers who eventually bought the map, actually lived. And judging by the degree of manipulation required to 'warp' the map on to a modern geography, it is least accurate in relation to the East End, the Eastern approaches of the Thames; and the rural areas to the North West of Westminster.

Surveying

John Rocque's claim was that he would follow a precise methodology:

The survey work began in March 1737 (new style 1738), and lasted most of a decade. In effect, Rocque was combining the two methodologies that form the basis for survey practise to this day. In contradiction to the order in which he described them, his initial approach involved a ground level survey using a chain and compass - taking direct measures of length with the 'chain' (actually a metal chain in the 18th century), and recording the angle of the line against a compass bearing. This ground level survey was then supplemented by a trigonometric approach which sought to divide the whole area of London in to separate triangles on the basis of a survey made from the tops of churches. This methodology involved using a theodolite to measure the precise angle between two points (church steeples in this instance), when observed from a third. By then moving to one of those steeples, and measuring further angles between further church steeples, it was possible to build a series of triangles with known relationships to one another. With a precise measured distance between any two points in any given triangle, it is then possible to calculate the distance between any other two points, and hence build up a lattice of known geographical reference points.

In practise these two methodologies seldom produce a result that align perfectly. Ground surveys, in particular, tend to magnify minor errors; while trigonometric methodologies tend to be self-correcting. In this instance, Rocque appears to have relied on a ground survey in the first instance; only to find that it contradicted his trigonometric measures, meaning that much of his early survey work had to redone. This substantially slowed down the work, and brought Rocque and his business partner to near financial collapse by 1742. The methodologies used also help to explain some of the consistent errors found in the map. A trigonometric approach worked well in the City and West End, crowded as they were with churches and their steeples; but was less suited to the rural landscape found to the East and West of the capital, with its limited number of identifiable vantage points. This was probably less of problem to the North and South of London, because of the rising trend of the land.

As important for historical research as Rocque's geophysical survey of the city, was the record of over 5,500 street and place names included on the map. The surveyors carefully collected and recorded local place names as they worked, and returned to check on their accuracy where these place names seemed to contradict those found on earlier maps. In the City, Rocque also had the advantage of the authority of the Court of Aldermen behind him, which ordered that the Beadles assist in the process of collecting and verifying these details. In the months prior to publication, the public was also invited to his shop in Hyde Park Road to examine the original drawings and offer corrections. For a detailed account of the impact of these production details on the map; and of how they shaped the process of turning an eighteenth-century map image into a fully warped and GIS enabled resource see Mapping Methodology.

John Rocque

Rocque was born in 1704-5 in Geneva, to Huguenot parents, and emigrated to London sometime before 1734 in company with his brother Bartholomew. Much of his early career involved drawing plans of aristocratic gardens. The project to map London was first agreed upon in 1737, and the survey began almost immediately. During the next nine years, Rocque divided his time between this London project and a series of maps and plans of provincial towns including Exeter, Shrewsbury and Bristol. The map of London was financed by subscription:

In the end, 246 individuals bought a copy of the map at this price, the list headed by Frederick, Prince of Wales, who later appointed Rocque as the official royal cartographer. John Rocque died in 1762 and his business was carried on for many years by his widow.

Further Reading

There is an extensive and detailed literature on John Rocque's career, on the financing of this and other projects, and on the wider history of maps of London.

- Barker, Felix; Jackson, Peter Charles Geoffrey. The History of London in Maps. London, 1990.

- Hyde, Ralph. Ward Maps of the City of London. London, 1999.

- Hyde, Ralph. 'Portraying London Mid-Century - John Rocque and the Brothers Buck', in Sheila O'Connell, London 1753 (London: British Museum Press, 2003), pp.28-38.

- Rocque, John. The A to Z of Georgian London. Lympne Castle, Kent, 1981. See Introductory notes by Ralph Hyde.

- Whitfield, Peter, London: A Life in Maps', (London: British Museum, 2006).

See also:

Footnotes

1 A Proposal, By John Rocque, Surveyor, and John Pine, Engraver, For... A New, Accurate, and Comprehensive Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster, and Borough of Southwark, 1740. ⇑

2 A Proposal, By John Rocque, 1740. ⇑

3 A Proposal, By John Rocque, 1740. ⇑

4 A Proposal, By John Rocque, 1740. ⇑